Casualties of War

Lahore today looks like a city at war. One of the greatest unacknowledged casualties of the United States’ “war on terror” has been the cities—and citizenry—of Pakistan. The US invaded Afghanistan in 2001 to oust the Taliban from power in response to the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center.[1] In 1985, sixteen years prior, President Ronald Reagan equated the Taliban mujahideen who had defeated the Soviets in Afghanistan as “the moral equivalent of America’s founding fathers.”[2] This presidential stance has obviously changed since. In 2008, the US committed another surge of troops to Afghanistan due to the continued presence of the Taliban in the region. Pakistani military operations were waged in parallel in the northwest regions of the country bordering Afghanistan. Since then, Pakistan has seen a particularly stark backlash within its borders as a response to its continued collaboration with its close ally.[3] Militants within Pakistan have retaliated by targeting police and security sites in cities throughout the country. Lahore is just one unsung casualty of this war that links Lahore and New York City across disparate geographies through the legacy of US policy and Pakistani collaboration during the Cold War.[4] As Eqbal Ahmed presciently said: “These are the chickens of the Afghanistan war coming home to roost.”[5]

Lahore is renowned for its food and its inhabitants’ penchant for pomp. It has been described as “the city of people who love unconditionally, without reserve, the ‘heart of the Punjab.’”[6] Unlike Karachi, its more populous southern rival, it is neither regarded as particularly violent nor cosmopolitan in the popular imaginary.[7] The writer Mohammad Hanif describes: “Half a dozen people are killed on an average day: for political reasons, for resisting an armed robbery, for not paying protection money, and sometimes for just being in the wrong spot when two groups are having a go at each other. If the victims don’t belong to your family or your neighborhood, or if you are not carrying out the killings, you are not likely to hear the gunshots. On television, you’ll catch a glimpse of ambulances…and you’ll thank God that it was a relatively peaceful day.”[8] Lahore has not historically experienced such incidences of daily violence and was instead wearier of attacks on its religious minorities that intermittently punctuated its past.

Beginning in 2008, Lahore experienced a wave of retaliatory attacks that were both unprecedented in scale and frequency.[9] The attacks were in response to Pakistani military operations that were perceived as occurring at the behest of the United States. The seemingly incessant bomb blasts that escalated from 2008 through 2010 gave rise to a public discourse of fear, anxiety, and paranoia, with a sense of incomprehensibility as to the reasons for the chosen sites of violence and dismay at their human toll. The repercussions of these blasts are now so interwoven into the daily experiences of the city’s inhabitants that youth, particularly, cannot remember—nor imagine—the city otherwise. The attacks have given rise to what I describe as Lahore’s architecture of in/security, which is reshaping the contours of the city as well as the way its inhabitants thread through it. This has continued despite the fact that since 2010 these attacks have abated. Bomb blasts today are no longer perpetual, and yet in effect they persist in the urban psyche and endure through the markers of securitization that populate this considerably altered city. It is increasingly difficult to gauge safety in Lahore, to situate the reality of lived experience against the symbols proliferating in the city that continue to mark it as unsafe.[10] The Lahore High Court in February of this past year even ordered the provincial government to remove security barriers and apparatuses that are obstructing the flow of traffic in front of administration and police headquarters throughout the city. The police and senior officials have refused this request and barriers remain in place.[11] Residential areas are another issue altogether.

[Entrance to Karbala Gamme Shah with security barriers and police. Photograph by Julius John.]

Lahore’s Architecture of In/Security

I am interested in the emergence of Lahore’s securitized zones and the way power inscribes itself in urban space through architecture. Parallel with this is my interest in using cartography as an analytic tool to interrogate processes of securitization. By architecture here I mean conceptual approaches to space, following Eyal Weizman’s definition of it in his work on Israel’s architecture in the Occupied Palestinian Territories: “On the one hand, the book deals with the architecture of the structures that sustain the occupation and the complicity of architects in designing them…On the other hand, architecture is employed as a conceptual way of understanding political issues as constructed realities…[where] the occupation is seen to have architectural properties, in that its territories are understood as an architectural ‘construction,’ which outline the ways in which it is conceived, understood, organized, and operated.”[12] Normative discourse responding to the bomb blasts in Lahore attributes the rise in securitization as an effective response to the attacks and also considers the city as a whole under siege. My focus in this essay is two-fold: one is investigating the process of securitization and its architectural effects, while the other is creating new representations of the city that allow us to queer our understanding of it.[13] By queer here I mean to see the city otherwise, to defamiliarize and consider it against its popular semantic registers within Lahori public discourse.

I treat the city of Lahore as an “elastic geography,” a dynamic entity that is both a physical site and imaginary construct.[14] I am particularly interested in the relationship between visual representations and our image of the city, and in using cartography as a tool to understand the way in which the securitization of Lahore manifests itself spatially.[15] New means of representation can create alternative images of the city, and my hope is that this provokes and challenges us to reconsider and ultimately transform the relationship that we have to space and power, from Henri Lefebvre’s writing on the “right to the city” to David Harvey’s insistence that “the right to the city is far more than the individual liberty to access urban resources: it is a right to change ourselves by changing the city. It is, moreover, a common rather than an individual right since this transformation inevitably depends upon the exercise of a collective power to reshape the processes of urbanization. The freedom to make and remake our cities and ourselves is, I want to argue, one of the most precious yet most neglected of our human rights.”[16] It is a markedly different thing to say that the attacks post-2008 in Lahore were primarily targeted at police and security services than to say that Lahore is being indiscriminately bombed. It is even more striking if this is supported by visual representations that aid in our analysis of security issues.

In Lahore securitization has become a primary method through which certain regimes of control are legitimized, which is what I refer to as Lahore’s architecture of in/security. This most visible manifestation of a regime of control is legible in the preponderance of security measures distributed throughout the city—walls, barriers, gates, and checkpoints. These objects and apparatuses—some cropping up overnight, others calcifying over time into permanent structures—are found throughout the city in residential areas, religious spaces, and governmental and police zones. They delineate boundaries, block vehicular and pedestrian access, restrict entry, and alter the city’s urban fabric. In civic spaces barriers and checkpoints effectively shrink civic space and encroach upon the rights of citizens. In residential blocks they indicate a family or larger community that is fortifying its boundaries. Parts of Lahore look like the city is at war because spaces are dominated by the presence of these objects and concomitant processes, which are the artifacts and performances of its in/security. This is further legitimized through a discourse of in/security by its multiple agents, state and non-state alike.[17]

[Datta Darbar (Datta Ganj Bahksh) fortified by concrete barriers and barbed

wire and heavily staffed by police. Photograph by Julius John.]

Let us begin with Lahore’s walls. Walls are interesting because they, at the most basic level, block you from accessing spaces physically but also deal with vision: they keep your eye from seeing through spaces. After the 2008 bombings, the city issued an ordinance to public institutions recommending that they increase the height of their walls from six to eight feet. Residential quarters took note and did the same. It is inconceivable that two additional feet of brick, sheet metal, concrete block, or barbed wire are increasing anyone’s safety, but the symbolic gesture of securitizing space is the more valuable one. If you look closely at the city’s walls, the brick and mortar betray their age and you can read the line at which the additional increment begins. This horizon line is legible throughout the city—a horizon denoting fear. The result of higher walls and the placement of boards to cover what was visually permeable before (the perimeter gates bounding Punjab University or National College of Arts) has been that if you are driving or walking along Mall Road, space has become flattened. It has no perspectival depth. This obliteration of transparency is a newer strategy of control that is moving from the physicality of the body to that of the gaze. Citizens are effectively cordoned off from using and even claiming these civic spaces now that they are no longer visible. Mall Road has become a purely symbolic space of power, evident during the spectacularized displays of fervor exhibited by “political” protestors who crowd the street, much to the chagrin of drivers, since all other spaces are barricaded.

The counterpoint to the fixity of walls in Lahore is the movable barrier—the checkpoint. Checkpoints have a ghostly quality in the city and can appear and disappear, expand and contract through the day and night. They exploit this architecture of impermanence and are perceived as temporary objects, which, if they are present in excess of years, they are not. Checkpoints, unlike walls, barriers, and the like, engage the social realm instead of simply blocking access to space or delineating boundaries. Checkpoints exclude, produce hierarchy, and restrict access. They also empower security services who monitor social behavior and control flows of circulation. Security details at checkpoints in Lahore routinely harass and demand bribes from drivers, discriminating based on class, likeliness of alcohol consumption, and perceived occupation of the driver. The public discourse on safety considers the bomb blasts as the result of actions of people from outside the city, non-Lahori’s, but through the infrastructure of checkpoints this is collapsed onto tensions regarding class that arise from within Lahori society.

[Concrete barriers and new concrete wall outside the FIA headquarters on Temple Road. Photograph by Sadia Shirazi.]

In the residential area of Cantonment, for example, checkpoints are now veritable tollbooths, with automated service lanes for residents. What was a temporary structure put in place after the spate of bombings is now concretized into a fixed entity. Defence Housing Authority (DHA) is another case in point. This residential development is owned and managed by the military and has checkpoints, guards, and barriers placed at points of entry between it and Charrar Pind, a village that predates the construction of Defence that is now strangulated by the constructions encircling it. Charrar’s inhabitants are now monitored as potential threats. The arrangement of concrete barriers forces people and vehicles to navigate around them at a clipped pace; the checkpoints here are slow spaces of compression that filter movement in one direction only. The residents of Charrar are de facto criminalized and scrutinized, since any departure from their settlement necessitates that they travel through Defence, which surrounds them and in which many of its residents are employed as domestic labor. In these sites of securitization, the threat is perceived from within and elsewhere. Charrar is elsewhere in a sense, but within and outside of Defence. These checkpoints are only visible to Lahoris who live or travel within this residential development and are targeting class difference exclusively, which distinguishes them from the temporary checkpoints that surface on Mall Road leading towards its civic spaces in colonial Lahore. The checkpoints in Defence and Cantonment are not part of public discourse on the rise of securitization after the pervasive bomb blasts. The larger discourse on securitization elides this internal friction between class and caste, village and military developers. The response from a perceived threat from inside is justified by focusing on threats from outside.

[Map by Sadia Shirazi.]

Cartography and the Spectacle of Security

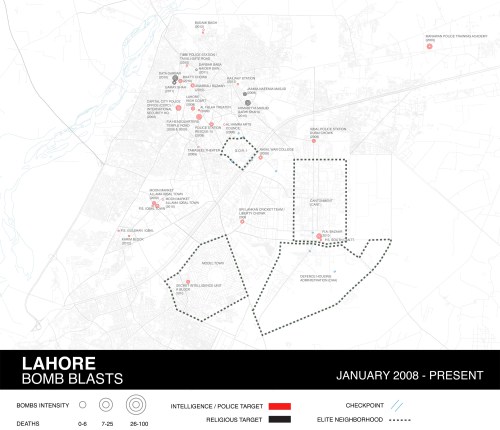

It was in response to heated arguments with my mother regarding whether and how safe Lahore actually was that I began a research and cartographic project about the bomb blasts.[18] I wanted to make sense of the paradigm of in/security and began to consider ways to visualize information regarding the blasts. First I combed through publicly available information on bomb blast sites, casualties, and perpetrators; I assembled the data into a table from 1997 onwards. In the span of ten years, from 1997 through 2007, I saw that there were only two bomb blasts in Lahore, both targeting the minority Shia community. These attacks occurred in 1998 and 2004 respectively. There were no attacks from 2004 through 2007. Beginning in 2008, Lahore experienced a series of high intensity bomb blasts concentrated in the colonial city at targets such as the High Court, Police Headquarters, and Federal Investigative Authority headquarters. None of the 2008 attacks targeted minorities. It was clear to me after completing the table that in 2008 the character, location, and intensity of the blasts altered considerably, which corresponded with the US surge in Afghanistan that same year and military operations conducted in coordination by Pakistan. Each subsequent year has resulted in an escalation of those attacks, from five in 2008 to ten in 2009 to fifteen in 2010, after which attacks subsided, with three most recently in 2012.[19] Most high-impact blasts were claimed—by militant groups ranging from the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan to Lashkar-i-Jhangvi—while others, such as the horrific attack on Datta Ganj-Baksh, also known as Data Darbar, a shrine revered by Sunni and Shia alike, are still unaccounted for.[20] A series of low-intensity copycat bombs, usually targeting cultural sites such as music halls and theaters, have also occurred that are usually unclaimed.[21] Visualizing the information made many things legible that were otherwise obscured.

One of the most striking things to emerge out of the articulation of the cartography of Lahore’s bomb blasts after 2008 was that most of the attacks in Lahore were targeting security outfits—the police, army, and security personnel. The first spate of bombings in 2008 hit police and security outfits distributed throughout the city. The bomb blasts from 2008 onwards were also primarily concentrated within the colonial city—built by the British—since many governmental sites and police headquarters are located there. The blasts that occur far from the colonial city are targeting security outfits that are located in residential areas as well, so civilian casualties are collateral damage. The reason for high civilian casualties in many bomb blasts is due to a number of factors. One is the fact that the colonial sites are densely populated, so civilians are literally everywhere and rarely travel alone but at a minimum in pairs. Another factor is that security outfits now have satellites in residential areas, where their presence imperils civilians as they attempt to gain cover by inserting themselves within residential and commercial areas. The 2008 bomb blast in K block of Model Town, a prosperous garden-town-inspired suburb of Lahore, was aimed at a Federal Investigative Agency (FIA) facility that also housed a US-counter terrorism unit. It was not a random blast in a residential neighborhood that includes the enclave of the Pakistan Muslim League (PML-N) Sharif family.[22]

The map also proved that the checkpoints that have arisen post-2008 have no correlation to the frequent sites of attack, but are instead demarcations of elite residences and neighborhoods. The resultant fortification of parts of the city only protects a small percentage of the population from threats. The fortified enclave of the head of the PML-N itself has caused consternation amongst the public as it extends outwards and blocks public streets at the periphery of their land, guarded by heavily armed police and private security forces with the additional deterrent of a brightly painted tiger replica that sits atop a column. Security checkpoints indicate rarefied spaces or crudely convey the exclusive nature of the spaces and the people’s status that they demarcate. As noted above, the checkpoint in Cantonment is now a tollbooth, for which residents purchase a pass that allows them through an automated fast lane. Securitization is shifting from a focus on citizens and terrorists to include the security of upper echelons of society from the lower, women from men, villagers from suburban residents.

[Barriers outside National Bank of Pakistan in a commercial area of Lahore. Photograph by Sadia Shirazi.]

One morning this past year right before the Monsoon rains as I drove to work, a route that used to take me five minutes took me forty minutes. This was due to a combination of security barriers and construction projects that were causing vehicular mayhem. I remember sitting in traffic, livid, cursing, and enraged, to little effect. At that moment I felt with overwhelming clarity that both security measures and horrifically planned civic “improvements” had similar aims—they inconvenienced exactly those individuals who they were symbolically intended for. Leaving aside construction projects, one has to question whether securitization processes indicate a safer city or one that is made all the more threatening through these devices. It is also crucial that we tease apart just whom the city is protecting itself from. I began this essay by writing that Lahore looks like a city at war. After having described both the increased securitization measures alongside the deductions I was able to make based on my mapping of the bomb blasts, the question that remains is—who exactly is the city at war with?

NOTES

[1] This essay is not an inquiry into the invasion of Afghanistan or its efficacy—it is now the longest ongoing war in American history—but is focused on the effect it has had on one particular city in Pakistan.

[2] President Reagan actually hosted the mujahideen in the White House where he announced to the press with the men standing before him their likeness to the founding fathers by saying, “These are the moral equivalent of America’s founding fathers.” Metaphorically speaking, of course, because they were dressed much as the Taliban dress today—vintage mujahideen. Eqbal Ahmed, Terrorism: Theirs and Ours, speech given at University of Colorado Boulder, 12 October 1998.

[3] A contentious parallel policy of the US’s War on Terror has been to conduct raids and drone attacks within Pakistan, violating the sovereignty of the country and further straining the relationship between the two nations. While Pakistan publicly condemns drone attacks, it has also been reported that the country secretly shares information with the US and/or allows drones to operate from their army bases with the consent of the Pakistani army, according to cables leaked by Wikileaks. The situation is complicated, to say the least.

[4] Eqbal Ahmed on this topic: “The reason I mention it [jihad] is that in Islamic history, jihad as an international violent phenomenon had disappeared in the last four hundred years, for all practical purposes. It was revived suddenly with American help in the 1980s. When the Soviet Union intervened in Afghanistan, Zia ul-Haq, the military dictator of Pakistan, which borders on Afghanistan, saw an opportunity and launched a jihad there against godless communism. The US saw a God-sent opportunity to mobilize one billion Muslims against what Reagan called the Evil Empire. Money started pouring in. CIA agents starting going all over the Muslim world recruiting people to fight in the great jihad. Bin Laden was one of the early prize recruits. He was not only an Arab. He was also a Saudi. He was not only a Saudi. He was also a multimillionaire, willing to put his own money into the matter. Bin Laden went around recruiting people for the jihad against communism.” Ahmed, Terrorism: Theirs and Ours.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ismat Chugtai, “Lihaaf,” City of Sin and Splendour, (India: Penguin Books, 2005), 174.

[7] It should be stated that these two things are not necessarily related. Despite the increase in violence, Lahore has not become more cosmopolitan.

[8] Hanif continues: “And just like any corner shop owner or cab driver, a writer needs a bit of peace and quiet to keep working.” Mohammad Hanif, “The Good Life in The World’s Most Violent City: Sweet Home Karachi,” The New Republic, 14 September 2012.

[9] These were in retaliation for Pakistan’s anti-Taliban military operation in Swat and other provinces that is perceived as occurring at the behest of the United States. “Taliban Commander Hakimullah Mehsud said the Wednesday morning attack in Lahore was payback for the ongoing military offensive in the northwest part of the country, which has become a haven for Islamic militants,” Mehsud declared. “If the government continues to carry out activities at the behest of America, we will continue to hit government installations.”

[10] It is the least safe city for its police and security officers, whose presence imperils the lives of the rest of Lahore’s inhabitants and who are lonely in public spaces, since no one likes to stand near them, particularly during festivals, processions, or protests.

[11] The Lahore High Court issued this directive after hearing a case of a woman’s death due to a traffic jam.

[12] Eyal Weizman, Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation (London: Verso, 2007), 6. Italics added.

[13] I consider my use of queer here as opening up an avenue to rethink the urban expansively and not only in regards to sexual orientation. Queer is used here as a political category, a “disorientation device” that arose out of queer studies and is influenced by Sarah Ahmed’s work on queer phenomenology. Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007).

[14] The “elastic geography” that Weizman writes about also applies to Lahore, where borders are neither rigid nor fixed but elastic and in constant transformation. Weizman, Hollow Land, 6-9. On the “urban imaginary,” see Henri Lefebvre, Writings on Cities (Oxford: Blackwell, 1996) and Cornelius Castoriadis, The Imaginary Institution of Society (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1987).

[15] I found the conversation between the Visible Collective and Trevor Paglen useful as a way of thinking through the perils of “mapping” and considering cartography as an analytic as opposed to authoritative tool: Visible Collective and Trevor Paglen, “Mapping Ghosts,” An Atlas of Radical Cartography (Journal of Aesthetics and Protest Press, 2008).

[16] David Harvey, “The Right to the City,” New Left Review 53, September – October 2008, 23-40. See Henri Lefebvre, Writing Cities (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 1996).

[17] Ibid., 5.

[18] All work that I do on Lahore is inspired by my mother, Sakina Ramzan Ali, and in honor of my grandfather, Doctor Ramzan Ali Syed, who, after seeing me when I was five, presciently told my mother that I was trouble. His hospital on Temple Road was damaged in the two consecutive bomb blasts that targeted the FIA headquarters further down the road in 2008 and 2009 respectively.

[19] Blasts from 2009 onwards did target minorities, particularly Shia and Ahmadiyya communities. The attack on minorities is a serious issue in Lahore and Pakistan at large. By focusing on the shift in violence in Lahore towards citizens and sites which are not religiously motivated, I do not mean to gloss over the importance of sectarian violence, but am interested in the way in which this violence has shifted and also entered into the everyday experience of all Lahoris.

[20] The Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) vociferously deny any hand in the attack, claiming that they do not target public spaces and only police, army, and security outfits.

[21] These are also called “cracker bombs.”

[22] Former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif is the head of the Pakistan Muslim League (PML-N).

[This article was originally published on The Funambulist.]